Nest Gets Into the Smart-Lock Game by Going Old School

Linus Yale Jr. founded his lock company in 1868. One hundred and forty-seven years later, the company continues to make locks—door locks, padlocks, safe locks—and some are a lot like the gear it made way back in the 19th century. But others are a little different. They're online.

Today, Yale, the company, unveiled a digital lock that taps into the "smart home" system designed by Nest. The Google-owned Nest makes Internet-connected thermostats, security cameras, and smoke detectors that also handle carbon monoxide, but that's not all. It also offers a variety of tools that let other companies connect their own devices with the various Nest gadgets. The idea is that you can control all these devices with a single smartphone app—and that each device can talk to the others. You can, say, set your security camera to start recording when someone opens your door lock—or program your door lock to say something when you step into a house full of carbon monoxide.

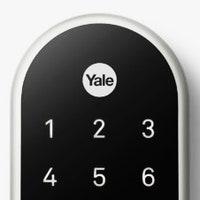

But the new Yale lock, dubbed Linus, is a little different from other devices. It's the first third-party device designed to communicate with Nest gadgets directly, via a wireless network set up inside your home. Previously, such devices could only reach Nest gear in a roundabout way, over the Internet. And this has its drawbacks.

Internet connections can be unreliable, and they're relatively slow. More importantly, tapping into the Internet via an ordinary Wi-Fi network requires a significant amount of power, which isn't always an option for digital door locks and other slim devices that run on batteries. But the Yale lock talks to Nest devices over a low power, local-area communications system called Weave, which was developed by Nest and uses a standard networking technology called Thread. Nest is now sharing Weave with a variety of device makers.

Meanwhile, you can manage and monitor the Yale lock from the same smartphone app that oversees the other Nest gear. Using the app, you can lock and unlock the device, distribute pass codes to family and friends, track who uses the lock and when, and, yes, program the lock to interact with other devices. "We're truly a part of the Nest ecosystem," says Kevin Kraus, who oversaw the development of the new lock. In other words, the Nest system continues to expand beyond Nest.

This points to a future where the smart home begins to make more sense, where it can appeal to far more people. Controlling your thermostat from a smartphone app is one thing. Controlling a wide range of devices from the same app—and arranging for communication between them—is another. It's a future that so many other companies are exploring. Apple hopes to facilitate much the same thing through a project called HomeKit. Others are linking myriad devices through technologies with names like Zigbee and Z-Wave.

The industry won't settle on a single technology that drives all smart home devices—at least not any time soon. But we are approaching a world where more than a few devices can work together. And that can make for a truly smart home. Nest will soon offer a central online store where you can shop for all sorts of devices that plug into the Nest system.

According to Nest co-founder and vice president of engineering Matt Rogers, more than 11,000 device makers have signed up to build compatible devices through the company's 16-month-old Works With Nest, and this includes everything from light bulbs to cars. For every eight homes that use Nest gear, Rogers says, one has already plugged this gear into a third-party gadget.

At the moment, third parties tap into the Nest system through the company's Internet APIs, or application programming interfaces. Internet APIs have long been available for the Nest thermostat and the Nest smoke detector, and today, the company unveiled APIs for its Nest camera, a device it acquired with the purchase of a startup called Dropcam. But for Rogers and Kraus, the possibilities are far greater now that Nest is sharing its Weave technology with outside companies like Yale, whose lock runs on alkaline batteries and mustn't burn a whole lot of power.

Nest's hope is that it becomes a hub for all your smart home devices, that you use its app to control every one of them. But at the same time, the company is giving device makers the freedom to offer their own apps. Though that's good for device makers, it shows just how complicated the fledgeling smart home market may become. Yale also builds digital locks that tap into Zigbee and Z-Wave, and these don't work with Nest. "We look at all the available technologies and do what the market wants," Kraus says. But smart homes that span a broad range of devices are now within reach. And as time goes on, that range will grow.