The wrong kind of rain: why Britain is not as wet as we think

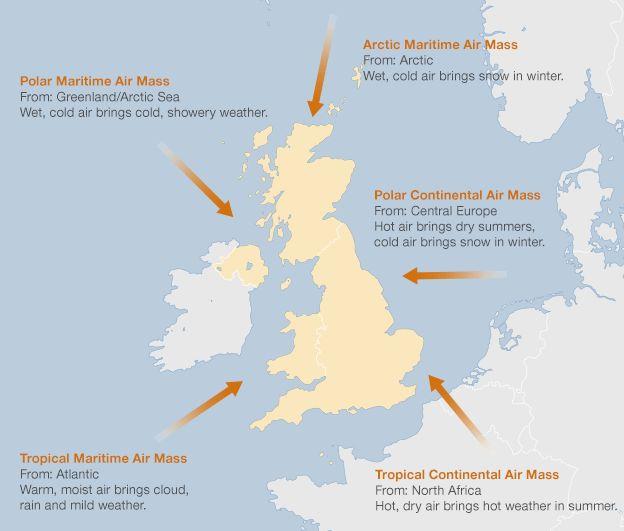

A running tap, a trickling toilet, a sprinkler left on overnight. We may think that wasting water shouldn’t matter in Britain because the one thing we have plenty of is rain. So why are the Environment Agency and water companies so worried about our water supply that they are actively encouraging us to use less water—a lot less? It turns out that while Britain seems to have more wet days than many of us would like, it’s the wrong kind of rain: too much, too quickly in winter―and then too little stretched over a long, hot summer. Climate change is driving our seasonal disparity to dangerous extremes so that we increasingly veer between contrasting crises of overwhelming winter floods and devastating summer droughts. This is cause for concern as two recent severe weather events show: the record-breaking drought of 2018 and floods of 2020.

Spring 2018 was typically wet, but within a few months the country was gasping for rain. Summer temperatures hit near-record breaking highs, and with soaring temperatures came drought. Across Britain, it was one of the driest May-to-July periods ever, and for regions like East Anglia, it was the second driest on record, resulting in toxic algae blooms to the Norfolk Broads and threatening to dry up the region’s iconic chalk streams. With the UK getting only about half its expected summer rainfall, water resources deteriorated rapidly. Major rivers in England, Scotland, and Wales hit record lows, and reservoir levels dropped significantly.

This brought fears for the domestic water supply as a thirsty nation turned on the taps to keep cool. While some water authorities were boosting supplies by an extra 87 million litres a day, consumers in some regions were drawing an extra half a billion litres: water restrictions in England were only narrowly averted. Soils dried out, damaging crops; drowned villages emerged from reservoirs; and the outlines of long-lost buildings appeared on the landscape like invisible ink. Seen from space, the country literally changed colour from green to brown: it was the UK’s longest drought in more than 40 years.